Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director general of the World Health Organization (WHO), used the phrase “window of opportunity” to describe the international community’s response to Coronavirus. As global fear about the unknown consequences has spread, we’ve seen stock markets take even deeper falls than during the 2008 financial crisis. Some companies are hit by crisis, while opportunities open for others: value of shares in companies manufacturing hand sanitizer and supermarkets have risen. The background is a fragile global economy with crisis looking imminent. The economy is burdened by corporate debt: “unsustainable accumulation of public sector debt and of debt in the non-financial corporate sector highlights serious vulnerabilities“. In UK, millions of people never recovered from 2008 crisis. Now, as Budget Day looms the government is stepping in to protect businesses, for example through tax credits. We need to organise to protect the health of our communities and build against “austerity mark 2”.

Crises provide political and economic windows of opportunity. Austerity is a neoliberal project through which ordinary people paid the banker’s debts following 2008 financial crisis. Since then, we’ve seen the billionaire elite class grow as poverty has deepened. What these inequalities look like in the UK has been highlighted by United Nation’s Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights: Phillip Alston’s, devastating report on poverty that names austerity as a political project.

That project is responsible for total public spending, as a share of GDP, falling from 44.9 per cent in 2009-10 to 38. 4 per cent in 2018, well below the EU average and close to the US’s 36 per cent; cuts of 49% in local government since 2010 and £20bn in welfare (child benefit worth less than 17 years ago). Before the Covid-19 crisis, this hard-right conservative government was planning 5% spending cut in all departments. This follows an average 20% since 2010. The 5% cut for Department for Education now threatens Universal Infant Free School Meals (UIFSC).

Why Covid-19 crisis?

Ian Goldin focuses on globalisation and the spectre of “risk” described by sociologist Ulrick Beck (see Risk Society). For Beck, the concept of risk changed with globalisation. Rather than individual, it is: borderless, global, uncontrollable, incalculable, uninsurable. Beck saw this with Chernobyl disaster in 1989 and spectacularly with climate change.

From a Marxist perspective, Covid-19 is viewed through dialectics. Change is constant and driven by contradictions. For example, Wuhan underwent rapid urbanisation, from 2 to 11 million people in 30 years. Mass urbanisation has contributed to economic growth. Dialectically, things can become their opposite bringing unintended consequences, in this case, contributing to global economic crisis. Is this health crisis due to rapid urbanisation with insufficient public health planning or democracy? Is this a case of “knowing what we know and doing little about it?” With continued drive on economic growth despite its consequences, are we ignoring the evidence about how pathogens cross animal-human interface? It’s a travesty of history that capitalism including its quasi-form in China repeats its mistakes and the working class and masses suffer.

Potential pathogens from industrial husbandry treated by chlorine.

The governmentalities perspective, based on the thinking of Michel Foucault, is often used to critically consider public health policies. It is similar to the role of ideology but its focus is on how the soft power of the state is wielded at the ‘micro’ level, that is, of the person. We do what those in power want, believing it is “free will”, “common sense” or for the “greater good”. We govern our “mentalities” through self-monitoring and self-regulation. Foucault highlighted disciplinary mechanisms, the role of the ‘gaze’, of surveillance: the power that is wielded in feeling that we may be watched. In managing this public health crisis, China has used sophisticated digital surveillance techniques. While China is commended for its containment of the virus, and with solidarity to the health workers and communities, ethical and political questions should be challenged post crisis. If we’re not careful, in face of Covid-19 we might see greater use of surveillance and new methods of social control in UK.

“The standard of justice depends on the equality of power to compel and that … the strong do what they have the power to do and the weak accept what they have to accept” is a truism from Ancient Greece; reinvigorated by Yanis Varoufakis.

‘The weak suffer what they must’ in Neoliberal England

For the Covid-19 crisis, a major concern is UK’s endemic social and health inequalities and the income precarity faced by millions. In London alone, 1.5 million adults (21% of population) and 400,000 children are in food poverty. Health inequalities include lack of access to a health system already in crisis. We need only think back to the crisis faced by those with mental illness whose welfare benefits were removed and faced tragic injustice; dying of starvation. Children in families with no recourse to public funds are denied free school meals. These examples show that those governments did not fundamentally care about hunger, the old, the ill or the young. This is neoliberal England before this new hard-right conservative government.

This government now attempts to manage the Covid-19 crisis with soft power of the Behavioural Insight’s Unit and hard power of troops. Drawing on Naomi Kline’s thinking (see the Shock Doctrine), we can imagine how they will use this crisis to progress the neoliberal project. As well as ‘experiments’ in controlling social behaviour might there be opportunities to restructure through technological, digital health innovations? Matt Hancock, Health Minister, stated the supermarkets will feed people who self-quarantine – an impossibility due to the lack of delivery vans – maybe we’ll see drone deliveries? Or maybe, these free marketeers will be paralysed if crisis is too large? Afterall, they’re busy making trade deals as we leave the EU. As with the aftermath of 2008 financial crisis, our money will be used to ensure capitalism progresses. We can be sure the working class will foot the bill.

What should food and health activists do? A political ethic of care.

We can be certain that working-class communities will suffer most. What should social justice, and socialist food and health activists do? Up against climate of panic and fear, there will be appeals for more volunteers to feed vulnerable members of our communities. The greatest solidarity comes from our communities but this should be political voluntarism as exemplified in history: Black Panthers and Miners’ Wives Support Groups (1984/5 UK Strike). In supporting others, we do so in political action, to defend our communities: a political, collective, class ethic of care. This counters the neoliberal politics of poverty that drives volunteer work as charitable action. Well-meaning care but one that is replacing public health nutrition.

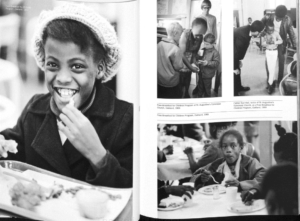

Panthers Survival Programmes: feeding children.

Miners’ wives support groups: Feeding community

The right to food is political. Who has that right is decided by those in power. Conservative governments have decided children in families with no recourse to public funds do not have the right to free school meals. In a food abundant society, what we eat, whether we eat, go hungry or starve are political decisions. So, politics should be at the forefront of our minds as food rights campaigners. This includes action in solidarity and organising through food. In turn this builds community and grassroots groups/networks. These provide the basis of local food democracy. That is, people making political decisions about the food and health needs of their communities and organising with others to get these. The Panthers had support from faith groups and businesses but their politics came first.

We should build a food rights movement that includes:

- Politicisation not charitisation: voluntary work as a collective, class and political act of care

- Strengthen our grassroots solidarity: democratically run community food and health support networks/groups

- Volunteers joining unions: Unite the Union – Community Sector

- Schools as centres of community nutrition: in many communities, schools have the only industrial kitchens and canteens capable of feeding our communities

- Councils should set needs budgets and use their reserves to support working-class communities

- Food activists – young, new, older or experienced – to stand for positions of power and influence

Covid-19: China and UK

What the Chinese government did was thought to be impossible, they contained the spread of the virus. Could/should these steps be carried out in UK?

- A lockdown of 50 million people since 23 January

- Two new hospitals with 2300 beds built in few weeks

- National mobilisation of health workers into Wuhan

- In regions beyond Hubei, self-quarantined people were monitored by “appointed leaders in neighbourhoods”.

- Movement was surveilled and restricted. For example, two widely used mobile phone apps, enabled the government to track and stop people with confirmed infections from traveling. “Every person has sort of a traffic light system. Colour codes on mobile phones—in which green, yellow, or red designate a person’s health status—let guards at train stations and other checkpoints know who to let through” in real time

- Home deliveries of food – albeit chaotic

- During lockdown people were allowed to group in their communal areas (although not for organised communal eating?)

What about the UK? For example, in a lockdown how would we feed our communities?

- Most boroughs have skeletal public health teams, including social nutrition

- Emergency food aid is provided through charities

- Panic buying will reduce the supermarket ‘leftovers’ for emergency food aid

- What happens to the children on UIFSC and free school meals?

Resilience Boards will no doubt have plans in place to ensure food supply. At the community level:

- Boroughs should carry out urgent and rapid assessments of nutritional needs within communities, and identify potential sites for the provision of localised communal food

- Immediate ward level meetings of food and health services: GPs, charities, councillors, schools, faith groups, parent/carers and others to set up ‘Food and Health Action Groups’ with democratically elected leaders to monitor local food crises

- Use the schools to mobilise parents/carers as invaluable voices of our communities

- Open up the industrial scale school kitchens and canteens so we may feed our communities in need

- Volunteering should be framed as political and not charitable acts. This could be enabled through the involvement of trade unions, specifically, Unite the Union-community sector, the NEU and Unison.

Our communities should not silently consent to UK government actions such as lockdowns and social control. The voices of the labour movement already advocate for entitlements of precarious workers. We should ensure that the voices of our communities in collective responsibility to care in solidarity are heard. We can only rely on ourselves.