Ten million voted for the Corbyn and McDonnell project. The vast majority of young people voted for progressive policies that focus on tackling inequalities, including inequalities in child health, through providing social rights that would reduce food poverty, halve food banks in one year and introduce universal free school meals (primary age). And, this to be integrated with a sustainable food system. Labour was promising a manifesto that would change people’s lives for the better on a scale not seen in modern times. Their policies ‘corbynomics’ are supported. The ruling elites and their class were desperate to avoid a Corbyn government and for these policies to materialise. It would have signalled the beginning of the end of neoliberalism in UK and be an international inspiration, not least in Europe. So, the hope was stopped by an orchestrated, vicious and hugely resourced campaign by the elites and their class that included the demonisation of Corbyn and used media and social media to manipulate, and fuel fear and social division.

This is not to idealise the Corbyn and McDonnell project. I am on the left, a socialist. I now wonder whether following 2017 election, the left leaders, advisors and strategists, including Momentum and we in the broader left, were sufficiently organised and understood the stakes, to the same extent as the elites, and Boris Johnson’s circle around ‘Britannia Unchained’.

‘Brexit’ was made to dominate. The reality was that for Johnson and co., Brexit was always a smokescreen for an agenda to deliver the UK to unfettered market forces. The sharks that are currently basking around UK waters will soon start to ravage the NHS, food system and workforces. All of which, and more, will be opened up to US standards. Already their commitment to increasing the national minimum wage and protecting worker’s rights have been axed. The agenda is further privatisation, deregulation and selling UK public services, land, assets and workforces to the highest bidders. That is the companies, US or other, whose profits will be made by driving down working conditions, increasing poverty, inequalities and social division. Inevitably, amid fightbacks, the government will increase repression and use the additional 10,000 new prison ‘spaces’ promised by Priti Patel.

I voted for Brexit- left exit – for an internationalist Left socialist UK government. I asked myself, how could I trust the EU capitalist powers, a trade bloc, that amid talks of human rights turn the Mediterranean Sea into grave yard (where 18,000 refugees have lost their lives since 2014). Some of my friends and family who voted remain swung behind Labour as they saw and feared the real Conservative agenda. Not following the national data, I thought this might be happening elsewhere. Labour supporters in Bermondsey (where I live) who had voted Brexit in 2019 Euro-election said they would ‘always vote Labour in the GE’. I thought at best we’d have a hung Parliament but not a defeat on this scale.

It’s important to remember that it was the crisis in the Conservatives, articulated through Cameron and Osborne, that opened the Brexit floodgates. Brexit quickly became a metaphor for the discontent and anger that many felt following decades of deindustrialisation, losing out in globalisation, and in a financial crisis that was made by the banks and paid for by the working class through austerity and precarity dominating every day lives. This social depression was caused by the very same politicians who then turned to populism and its false promises.

This pattern of events is not unique to the UK. Similarities across Europe point to the rise of nationalism and populism amid deepening inequalities. For the UK, there is irony that the one-nation Toryism is driving a rise in English nationalism, potentially leading to the breaking-up of the UK. Going into 2020, nationalism and inequalities could be compounded by the precarious state of the world economy as described by the IMF . And in the UK, growth (GDP) is forecast to slow from 1.3% in 2019 to 1.0% in 2020. This is the weakest since 2009. So, as Brexit unfolds the economic conditions within which it sits, are likely to worsen the effects on British workers and working-class communities.

What are the consequences for food and health inequalities?

The effects of Food Brexit disrupting the logistics in multiple and complex global food supply chains could lead to food shortages, increased food insecurity alongside spikes in food prices. In a globalised world, the UK food system relies on importing about 40 per cent of all the food we eat – an increase from around 25 per cent two decades ago. More than 30% of all the food consumed in the UK comes from EU member states. In London around 10% of jobs are in the food sector which contributes around £20bn to the London economy. The value of the U.K. restaurant market could lose £5.4 billion in the event of a “disorderly” Brexit. With food sector reliant on a migrant workforce, over one quarter made up of EU citizens, there will be a skills gap and labour shortages which bosses may view as an opportunity to replace with automation rather than paid workforce. Workers and their families will suffer the effect of price rises, and increased lack of access to affordable foods of good nutritional quality. Public sector food provision such as in schools and hospitals will be vulnerable to decline in nutritional standards. The poorest families and their children will suffer most. And, its important that we understand that the Conservatives do not care. They believe poverty and inequalities are inevitable and necessary. The poor are so because of ‘personal failing’ whilst ‘the most talented’ can lift themselves out of poverty. So, it is no accident that Conservative leadership does not consider the effects of Brexit on food security.

The US provides a warning for how UK society might change as inequalities and poverty deepen. Phillip Alston, UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights produced a damning report on the United States that shows how the deepening of poverty and inequalities is structural, that is, those in poverty stay in poverty throughout their lives. Significantly, alongside of this there has been an embedding of an ideology that blames people for their poverty – on a scale not yet seen in the UK: “Most Americans don’t care about it. They have bought the line peddled by conservative groups that poor people deserve what they are getting,” . In UK, this notion of individual responsibility and failure is increasing, in contrast to awareness of poverty as a structural problem and a political decision. The notion of individual responsibility, blame and failure is reinforced by a public health prevention approach that is centred upon behavioural change (forthcoming blog). Blaming the victim, is amplified through symbolic violence and stigma and played out in physical violence such as slashing the tents of homeless people.

What’s to be done?

Leading food poverty campaigns are organised and pressuring the government for national food hardship funds amid real concerns that charitable donations dry up. Local boroughs and regions have Resilience boards whose responsibilities include food supply. But now Brexit looms we need to consider whether these are comprehensive and meet the needs in communities.

There is a flourish of appeals for volunteers and contributions to charities. Volunteering is well established in the UK with nearly 40% of people formally volunteering with groups and 53% informally volunteering. It is gendered work with more women likely to volunteer. Most volunteers are from higher-socio economic groups, that is middle classes. However, working class communities are also rich in volunteers who step-in to fill the gaps such as created by privatisation of public services. Such is the case for many ofour community centres today. At times of crisis, such as during the Grenfell atrocity, free food is provided because of an intrinsic ethic of collective care and solidarity in our working class communities.

As poverty and inequalities deepen, and we organise to support each other, we should think about the ideological platform we use and messages it is sending. Is our food activism underpinned by solidarity, collectivism, social justice, rights and empowerment or by individualism, such as through acts of charity, which unintentionally reinforce ideas of people as deserving and undeserving? I consider both to be political. The former a socialist or progressive left platform and the latter fits neoliberal ‘Big Society’ approach that performs a symbolic violence on citizens in need.

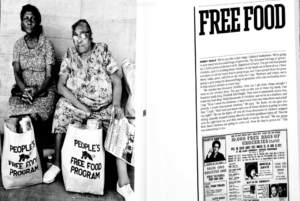

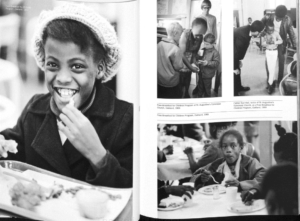

We can look again to the US, this time, for their experiences of community food activists. The grassroots Community Services Unlimited (CSU) founded by the Black Panther Party, promotes a social justice agenda and then seeks support for funding; including from charities and faith organisations. In the 1970s, the Black Panther Party provided national network of breakfast programmes and free food projects. The breakfast clubs centred on the rights of children to nourishment that underpins their capacity to learn. ‘Food’ was also a means of educating and organising community. For example, the clubs would sign up parents for voter registration and discuss Black Panther Party ideas. The Panther’s ‘Free Food Programme’ distributed tens of thousands of food parcels consisting of foods donated by local businesses. They would organise boycotts of food shops that refused to contribute. Their stance in supporting their communities was firstly a political act that was then supported by church and businesses. Before its appropriation by neoliberalism as introduced by Tony Blair and ideas of New Labour in government 1997-2010 this form of community ‘partnership’ worked well.

These days, similarities with the Panthers’ work may be drawn with Paulo Freire’s approach – Pedagogy of the Oppressed 1 : through co-creation between activist and community, a critical consciousness among the oppressed communities is developed, through which people question power structures. The personal becomes political2.

Brazil had progressive food policies that prioritise child health3,4. Nutrition and agricultural reforms that were made by Worker’s Party administrations in 2000s but now under threat by far-right Bolsonara government. Important for us today, is how these policies were born from a social movement, of national campaigns against hunger in the 1990s. These gave rise to CONSEA – the National Food and Nutritional Security Council of Brazil. It was born out of struggle, committed to fighting inequality and food insecurity. It operated at national and local levels through participatory principles until removed by Bolsonaro in January 2019.

UK has its own strong tradition of working-class communities collectively organising for affordable, safe foods. In the 1840s, Cooperative movement began in the Lancashire cotton mills providing affordable butter, flour, sugar, oatmeal and candles. By 1900 the movement had 2 million members. Alongside the cooperative movement, the trade unions have struggled for the basic right to food. Even for children, this is not a given. For example, in 1912 the National Union of Teachers supported introduction of school meals for reasons including the effect on ‘better bodies and better manners’ 5. In the 1930s, the TUC carried motions on mothers’ nutrition6. Following the interwar industrial and social struggles, nutritional standards for school meals were set in 1941 and in 1947, followed by a heavily state-subsidised school meals programme7. Only later to be eroded under Thatcherism, rebuilt by New Labour and since then, consecutive conservative administrations continue to weaken standards.

In the 1980s, the miners’ wives organised support groups who took collective action to feed their communities so that hunger would not break the strike. Today, branches of Unite the union community sector provide emergency food aid. In the US, some of the trade unions play a very significant role in organising food access in oppressed working-class communities. These examples will be elaborated in further blogs but for now, suffice to show that the right to food has been a core issue for the trade union movement. Outside the trade unions many take action to support developing a local food economy but mostly do so through quasi-private initiatives such as social enterprises and are thus not sustainable. For example, the Community Food Growers Network in London has around 2000 members but projects have short term funding. Going forward, I argue the trade unions should play a greater role, as class based organisations, they can help shift the narrative away from charity to social justice and rights.

For whatever reason we work in communities, I argue that we now need to do so from a political, social justice and empowerment approach. For well-meaning volunteers, a charitable approach unintentionally can reinforce a neoliberal ideology of the deserving and undeserving poor with devastating effects around stigma and social division.

Ideas for how we can organise

- Community food as a political project: Set up a joint platform for food activists, including faith groups, that begins to change the narrative in providing community or social nutrition away from charitable acts to political acts. For example, can ‘food banks’ become ‘food rights and justice centres’? The language we use can be a form of soft power that sends message of control and disempowers those in need. So, unintentionally, well-meaning people can patronise and label people as deserving and undeserving of help. Instead our relationships can be built on solidarity and collectivism through political platform of social justice rather than charity (although might be funded by charity and churches) that politically engages with communities in need and facilitate their power to organise.

- Collective and political ethics of care: Collective care through the sharing of food is commonplace in working-class communities. We often talk about collectivism and solidarity but now need to include a political ethic of care that centres our care work through food as part of the economy. We should reject the idea of voluntarism becoming structural and replacing the social state. All care work should be paid. As these ideas develop through our actions, they would become policy for the Labour and trade unions and for Left Labour government.

- Schools as centres of community nutrition: Many communities have lost children’s centres and community centres through spending cuts in local government. Schools remain but many are privatised into academies. We should consider whether schools should serve communities or a political agenda? It is likely that in most areas, schools have the only industrial kitchens that are suitable for cooking and feeding in bulk, as well as canteens and space for community to meet. Thus, they should be used for emergency food aid and broader community nutrition. Already, 100s of teachers support children who are hungry. This role for schools should be organised, for example, through setting up school poverty action groups that provides support to families.

- A strategic approach: At the moment feeding our communities in need is a postcode lottery. This means whether you go hungry or not can depend on where you live. A strategic approach is already adopted by London boroughs and London as a region, but what is the direction of travel? Is it towards more voluntarism based on charity ethos? Ethically, can we continue a postcode lottery in hunger and health? To counter this, pan-London action should be taken by Mayor of London organising with the London Labour councils and schools to guarantee the right to food.

- Universal Free School Meals: To feed children for health and learning is a basic minimum for a civilised society. At present, taking London as an example, UFSM is a postcode lottery with only four Labour councils providing these for all primary school children. Other Labour councils prioritise ‘holiday hunger’ whereby they provide free lunches throughout the holidays. This should be part of London strategy.

- Where will the money come from? Would the pragmatic approach taken by the four Labour councils who provide UFSM suffice for whole of London? Or, given that London is one of the most unequal cities in the world, would the most well-off agree to pay more council taxes? In the interests of social justice, Labour councils could appeal to the more affluent, through a referendum to increase their share of the council tax. This could include equal food rights and food justice, and finance universal free school meals. But would this provide the scale of support that is and will be needed? Alternatively, nationally Labour councils have resources of £21bn in unringfenced reserves and could legally set deficit budgets based on needs. This could open the way for a pan-London approach that in the very short term can tackle food poverty.

- An immediate conference of community food activists, trade unions, Labour Councils, and the Mayor’s office to discuss these and other ideas that will organise our communities.

These are just a few ideas. We need to start identifying how we can support each other in times of crisis and how we can change the narrative so that we build Left movements through the focus on food.

In my doctoral research working-class parents said ‘we need a food revolution’. There is indigenous food knowledge and all parents had creative ideas for cultural and nutritious foods that should be available on their high streets. They believe they should be involved in policy-making through forums at schools and children’s centres.

Finally, ………

We’ve always been involved in food, because food is a very basic necessity, and it’s the stuff that revolutions are made of.

DAVID HILLIARD, former Chief of Staff , Black Panther Party8

References and notes

1 Freire, P. (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Third edn. USA: Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd.

2 Ledwith, M. (2011) Community development: A Critical Approach, Second Edition. Policy Press: Bristol.

3Leao, M. and Maluf, R.S. (2012) Effective public policies and active citizenship: Brazil´s experience of building a Food and Nutrition Security System. Brazil: Oxfam. (Accessed: 4/10/2017).

4Sidaner, E., Balaban, D. and Burlandy, L. (2012) ‘The Brazilian school feeding programme: an example of an integrated programme in support of food and nutrition security’, Public Health Nutrition, 16 (6), pp.989-994.

5 Smith, D. (1997) Nutrition in Britain: science, scientists, and politics in the twentieth century. England: Routledge. p.17

6 p.103

7 Crawley, H. (2010) ‘Supporting Standards: an agenda for government’ in ‘Supporting Standards: an agenda for government’ Growing Pains. England: Food Ethics Council, pp. 4-5.

8This quote is borrowed from Garett Broad’s book ‘More than Just Food’. As a scholar activist, Broad, explores food poverty and the community food sector in USA. His case studies inlcude the CSU, founded by the Black Panther Party and poses social justice agenda in contrast to charity.