Omits the Right to Food

‘The Plan’ is insufficient to tackle England’s growing nutritional crisis

Critique

This focuses on reasons why the recommendations will do little to tackle England’s household food insecurity, food and health inequalities and growing nutritional crisis. The authors of The Plan come from a ‘kinder capitalism’ standpoint and sincerely want to reduce diet-related health inequalities. Yet we have a government that is not going in that direction.

This blog follows on from the short version, providing greater critique. Sections below can be read selectively by clicking on the section heading. The Plan follows Part One that amid the pandemic and UK leaving the EU, reviewed food insecurity and trade in July 2020. This blog uses these abbreviations: P1 for Part One & TP for The Plan.

Right to food

Schools

Free school food – universal and comprehensive approach

Schools as community hubs and centres of community nutrition

School food competitive tendering: is more competition really the answer?

Food and nutrition: heart of school life

Community

Medicalisation of food and prescription …again!

Shift to Primary Care Networks and more competition?

Healthy sustainable diets & food democracy

Failure of public sector procurement

Changing behaviours: corporate and communities but not political?

Obesity, stigma and inequalities

Investment needed

Austerity and local government spending cuts

Conclusion

Radical change, state responsibility& the Right to food

What to do next

Right to food

The crisis in England’s food and nutrition system has sadly not been tackled by the NFS. Nor has it tackled how we can build sustainable food systems within our cities, local authorities and communities. It has avoided recommending the government enshrines the ‘Right to Food’ in UK law. An opportunity painfully missed. One that could inspire millions of young people and build a social movement based on the solidarity and collectivism which exploded during the pandemic as caring communities took responsibility to feed all in need. It would be bedrock to the recommended new governance structures and legislative framework – ‘Good Food Bill’, impact assessments and institutional changes (TP p163). It could hold government to account especially when tackling inequalities. Right to food should be a central driver in transforming the food system by engaging society from the bottom up to co-create local food economies based on need, health equity, social goods, food innovation and sustainability, with for example, schools as centres of community nutrition.

Going forward, the right to food at local levels should underpin the food strategies that The Plan calls for (TP p163). Its local meaning can be worked out by local authorities, food businesses, public health food teams, trade unions, parents/carers, young and older people across England’s diverse communities. As it stands the lack of enforcement of the Right to Food provides scope for UK government to tackle food insecurity as seen fit by its politics and ideology.

A kinder UK capitalism?

It is clear the authors of The Plan lean toward a ‘caring’ capitalism. Testimonies speak to the sadness, desperation and neglect that many people feel as they struggle to eat and pay everyday living costs, and tell of the crises they face as health, social and welfare services fail them (P1 p55). It voices a moral responsibility to tackle the indignity of food poverty and food banks (P1 p55). The strategy is described as ‘interventionist’ (TP p12) alongside of supporting the free market. It possibly sits with the school of thinkers who argue capitalism needs to shift away from the classical neoliberal belief that the free market maximises human progress. Instead, state can co-shape markets and adopt a more collaborative approach between private and public sectors around key values for the common good (for example, Mazzucato, 2021; Elkington, 2020; Henderson, 2020).

The Plan links ill-health, and climate change, to the food system. It says the link it not ‘a corporate conspiracy, dreamed up by an evil genius bent on making us ill. It is the economics of supply and demand’ (TP p42) and the ‘unintended consequences’ of the food system. This indictment of the market approach to public health is illustrated by recognition that privatisation of procurement has failed health. Long-standing privatisation policies, characterised as ‘best value’ are to be reformed. Recommendation 13 calls for reform of public sector food standards, including schools: ‘The Government should reform its Buying Standards for Food so that taxpayers’ money goes on healthy and sustainable food’. This challenges the meaning of ‘value’ as quality and not just cost (TP p.252). The Plan further illustrates market failure saying that food businesses ‘want to do things better’ but are fearful that in making foods healthier they will be undercut by competitors. So, government should create a level playing field (TP p.10), that is intervene in the market. It explains other influences that can shape the market and drive change within food businesses. For example, Good Food Bill includes provision for government to collect new data from large companies about nutritional content of their produce and food waste to inform shareholders whose action can drive ethical change (TP p210). These tensions and contradictions within the market make change difficult. Trade-offs are made. Inequalities continue: ‘economic inequalities are not about to vanish’ (TP p62)’. In the absence of paying living incomes and welfare to tackle inequalities, ‘there is a particular urgency to the problem of helping low-income families to eat well’ (TP p62).

Despite these problems The Plan suggests a shift is needed away from pre-pandemic policies (austerity and privatisation). But is this in line with UK Government? During the pandemic, government intervened to save the UK economy and now returns to its free-market fundamentalist approach- ‘Britannia Unchained’. A new Tory right which has been exposed as crony capitalist: ‘extraction’ capitalists systematically under/disinvesting from public goods and has cruel hostility to those ‘most in need’: asylum seekers and refugees. We’ve seen the reintroduction of public sector wage restraint post pandemic as food prices begin to rise. Sadly, we cannot have illusions that UK government reception will be received more than what is politically expedient.

‘Cash first’?

Rich evidence is provided about food poverty and diet-related ill health. The Plan states that ending poverty will end food poverty. It agrees a cash first approach is needed: it is a ‘complete myth’ that income is not important to access healthy diets (TP p63) and a ‘strong economy and a benefits system’ is needed (P1 p55). However, the UK’s welfare system has been dismantled since the 2008 financial crash and despite economic growth (measured by GDP and profits) social inequalities and food poverty have deepened. Poverty, thus food poverty, are not inevitable but are political choices as spelt out by Un Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Hunger in the UK. Poverty is lower and inequalities reduced in countries with strong welfare states. The Plan does not set out what sort of economy, measurement of growth and benefit system may reduce poverty.

Paradoxically, a cash first approach – a living income as wage or social security – was not within the remit of The Plan. This raises cynicism about the purpose in commissioning The Plan. Together with omission of ‘right to food’ this shows a political direction that will not tackle food and health inequalities. The Plan acknowledges levels of inequality are endemic and asks that a: ‘generation of most disadvantaged children do not get left behind’. So, what happens to the least disadvantaged? The Plan leans towards a ‘nutritional safety net’ that prioritises feeding children in ‘poor households’ (P1 p56). During the pandemic this was defined by providing free school meals to every child up to age 16 whose families are in receipt of welfare benefits (P1 p88). The proposed income threshold of £20,000, post pandemic, is a trade off because of the pressures on public finances (TP p151), in which children are left behind.

Source TP p211.

The extension of Healthy Start Scheme is welcome, as is any small step that alleviates poverty and enhances maternal and child nutrition. These continue as means tested, ‘safety net’ measures which are stigmatising and produce social division, in contrast to universal rights to nutrition. Real living incomes and welfare are needed that cover the costs of nutritional needs throughout the life. Alongside checking that needs are met for example, a comprehensive programme to assess nutrition needs of whole community: mothers, children, families, and older people.

Schools

Against the backdrop of austerity and privatisation of education, including school catering and the entry of multinational food companies such as Chartwells/Compass into nutrition education, The Plan, takes a broad approach that promotes the health of children throughout their education years. That approach continues to be vulnerable to the ‘postcode lottery’ in nutrition provision and nutritional inequalities.

Free school food – universal and comprehensive approach

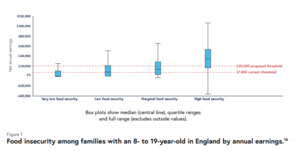

Universal free school meals continue from reception to Year 2 and The Plan recommends that eligibility is extended to all children up to age 16 years whose family are in receipt of benefits and earn less than £20,000. Due to economic pressures on the government this criterion has changed since Plan One that argued eligibility for all in receipt of benefits to age 16 years. There is plenty of wriggle room between the current £7000 threshold and proposed £20,000 for the government to change or not according to political expediency.

In contrast, the Right to Food Campaign argues for universal free school meals for all in compulsory education. I would include all young people in further education because nutritional needs continue throughout adolescence. Universality is the only way to end stigma, both the feelings of shame among young people and of social division between young people. Social division is mediated through food policies as illustrated by the denial of school food to children in families with no recourse to public funds. Further, as education and health are universal rights both of which are enabled through nutrition then it follows that school food should also be universal. There are long term social and economic benefits through universality. If as The Plan recommends, government pays for the ingredients in children’s cookery lessons (TP p148) stigma and social division would be reduced.

A comprehensive approach to school food would bring together all of the provisioning around breakfast clubs, fruit snacks, lunches and holiday meals. While every incremental step in providing children with food is welcomed, addressing diet related inequalities requires universal and comprehensive approach. This together with strategic approach to procurement within local authority areas would place schools as anchor organisations in developing local food economies.

Schools as community hubs and centres of community nutrition

The Plan argues that ‘Change starts at a local level, with talented and dedicated people’ (P1 p12) and that this energy can connect with neighbourhoods, communities and professions. This resonates with schools as community hubs and centres of community nutrition. This approach should be part of local and education authority strategies to co-ordinate around local needs and developing local food economies and skills. However, at present many schools manage their food provisioning in isolation with different food contractors and no access to their kitchens by their neighbourhoods because they are controlled by private contractors. In contrast the Right to Food campaign argues school kitchens should be used by communities. This is supported by national research among formal and informal public health nutrition workforce of whom 83% agreed school kitchens should be used to feed people in need as part of a co-ordinated local, regional and national food strategy (Noonan-Gunning et al., 2021).

School food competitive tendering: is more competition really the answer?

The Plan states the public sector has a ‘colossal’ food budget, and that procurement standards should be tightened-up to tackle poor nutrition standards that, for schools, came to light during the pandemic.

Source: Roadside Mum

The problem is lack of competition due to monopolisation with the domination of few large companies supplying the schools: top four contract caterers (Compass Group, Sodexo, Westbury Street Holding and Elior) have 61% of the contract catering market share (TP p253). The school catering market, driven by central government spending cuts and privatisation, is based on lowest possible costs. So size matters – economy of scale – to achieve ‘best value’. Recently the London Borough of Lewisham re-awarded the school catering contract to Chartwells (Compass Group) despite the scandal of free school meals food parcels during the pandemic ( March 2020 and January 2021). Compass have held the contract since 1999. No other companies tendered for the contract most likely because costs were too high and profitability low. Similarly, Holiday Activities and Food funding is not competitive and drives down workforce conditions. In my experience, this grant does not adequately cover costs per child. Outputs described in The Plan (TP p5) cannot be reached without using unpaid labour (volunteers), precarious labour and short-term contracts. This free-market approach exploits the feeling of collective responsibility to care for children in our communities. This is not sustainable and is counterproductive for child health. More competition is not the answer. Privatisation has led to monopolisation. Breaking the monopolies to create more competition only reproduces the cycle back to monopolies and drives down working conditions and exploits free labour. The problem is the ethics in making profits from health. Only the state can assert food and health security through an ethic of care based prioritising child health, not profit.

Food and nutrition: heart of school life

Giving food and nutrition knowledge and practices a central place in schools is important in developing young minds around science, skills, connecting with nature and planet, social nutrition and food sharing. There are wonderful examples of individual schools that integrated food – in all its meanings – to their curriculum and school life. Food A level is a good step forward to inspire young minds. However, schools face huge budget challenges and pressures resulting from the crises in social and economic conditions stemming from central government policies. Funding and resources are needed rather than Ofsted validation for food and nutrition.

Community

Working with communities has been at the heart of public health nutrition for decades. Indeed, the history of tackling hunger and food adulteration in England lies in the working-class industrial towns and villages, and early trade unions in the 1800s. This involved organising the distribution of foods which are safe to eat – that nourish rather than harm. These are actions of collective care and responsibility, of solidarity and mutual aid, of informal care and help practices. Fast forwarding to 20th century examples of collective care through food is exampled by Black Panther Party’s Survival Programme in USA in 1970s, Miners Wives Support groups in UK in 1980s and at Grenfell.

Collective action: Free food provided by the Grenfell community

Historically, alongside spontaneous social, informal care, medical model around nutrition science evolved with formal care (nurses and early nutritionists) provided through charities and early state interventions. Coveney (2006) discusses the history and tensions between social and medical models, the power held by different knowledges and experiences and the practice of ‘nutritional policing of communities’ as a governmentality; a form of soft power through which we self-regulate. In 21st century, dietary practices of ‘poor’ families are constructed through policies that mediate which types of foods are available and affordable on our high streets, and the data through which companies track and reinforce habits (for example, Mahoney 2015). So, our food choices are not passive but complex. As The Plan says, that includes training young advertisers in the ‘consumption effect’ (see below). Political decisions are critical around which foods and knowledges are made available to us. Decisions which are underpinned by structural factors of power, class, race and ethnicity.

Juxtaposed is the social action around food in our diverse communities, with range of food knowledges that come together in solidarity and care. For policies that enable communities to ‘eat well’ it is critical they are democratically engaged with, and involved in developing local food economies to meet their needs. This involves engaging young minds on our estates in thinking about future food system, the role of meat and innovation around protein alternatives, and more!

Losing the prevention focus

Report makes points that only 5% of NHS budget is spent on prevention and new funding is needed for community food and nutrition (p152). This point is critical. The loss of prevention focus was found in recent research by Future of Public Health Nutrition (Noonan-Gunning et al., 2021), along with reduced service capacity as needs increased with growing food insecurity since 2010. This research found dysconnectivity through the public health nutrition system, and formal structures are disconnected from community. The recommendations for new community level projects are welcomed but The Plan appears not to have drawn on extensive, rich experiences of what has worked well in recent decades. It is critical that this institutional memory of PHN system is not lost but is built upon with new experiences and resources.

Community development was integral to health promotion around public health nutrition in 1990s and early 2000s. When I trained as a dietitian in mid 1990s the Bolton Community Nutrition Assistants (CNAs) were working with mothers and families in their homes and communities. The CNAs were part of informal help (experienced lay workers) network who provided links between the formal (dietitian and health professionals) and communities. They were part of a large network of lay health workers in voluntary and paid capacity (see Kennedy et al., 2008, Kennedy 2010). Further example, by Davies, Manani and Margetts (2009) who developed community-based, peer-led approaches to improve the iron status of South Asian mothers. These works were built upon by Sure Start programme that integrated nutrition with peer mentoring and specialist fields developed around community dietetics and public health nutrition.

With austerity and privatisation many of these paid informal and formal posts were lost. Pre pandemic the numbers of unpaid informal helper increased. For example, Trussell Trust alone has 28,000 volunteers (Trussell Trust, 2021). These numbers increased again during the pandemic – a growing food voluntariat – together with formal helpers, a potential social food movement. Whether this movement develops or not, we should recognise these informal helpers hold the experience and ideas to contribute to PHN system at community level. So rather than ‘link workers’ that teach us what to eat (as report suggests), we need to engage with the movement of informal helpers, bringing together the recent experiences with past decades for a dynamic and exciting approach to community food security. This should inform prevention strategies which should be co-ordinated at local authority level and be fully funded.

The recommended approach is not connected with communities instead disenfranchises their voice and delegitimates their solidarity, collective responsibility and care. It emphasises an individual rather than collective responsibility at a time when collective action is needed.

Medicalisation of food and prescription …again!

The medicalisation of food has long been challenged and the prescriptive approach to behavioural change abandoned. Prescription wields a symbolic power and injury through stigmatisation already produced by referral systems and vouchers for food banks and Healthy Start scheme. Food education should be community and peer-led as in the past. So, this a backward step. Instead of Right to Food it builds on Victorian values of deserving and undeserving. It nourishes social division at time when we are experiencing inspirational collectivity through food sharing and care for nutritional wellbeing.

Shift to Primary Care Networks and more competition

Responsibility for public health nutrition was transferred to local government in 2013. The Plan does not explain the shift to Primary Care Networks that medicalises food and further fragment local services. Through free market approach of competitive bidding (that is failing to deliver public services) PCNs will bid for funds for community food projects. Already existing projects are underfunded with a precarious existence through short term grants and a reliance on charity and volunteers. The competitive approach has not supported joined up strategy or made it easier for communities to access affordable nutritious foods. Instead, we see a fragmentation of services, post code lotteries in access, reliance on low wages and volunteers. A consequence is that responsibility falls onto the communities to care for each other.

Food swamps & BOGOFS

In setting out the dietary inequalities in England, The Plan refers to the higher density of fast-food outlets in areas of deprivation, naming these as ‘food swamps’ (TP p.62). This is known by Public Health England for nearly a decade yet there is no discussion about the proposed reforms to planning system, Build Better High Streets or other, and how this will change ‘food swamps’.

Examples of food deserts and targeting of deprived communities with ultra processed foods (and alcohol)

The Plan exposes how young marketeers are educated in the ‘consumption effect’ – the more food you have at home the more you eat – and links this with BOGOFS. Thus, food companies are using psychological means to exploit bodily innate tastes and appetites and exploit people in poverty. They are knowingly promoting health harming foods onto poor communities. This is not news to people living in deprived communities who feel they are manipulated and discriminated against through food. From my own research with working class parents with higher weight ‘obese’ children (Noonan-Gunning (2019):

Felecia:

They’re [the government] not helping, I love cooking and find it better to cook at home… when tired I go to fast food shops, can’t be bothered to cook. But I like to cook stuff at home so I know what’s going in. I see my kids growing up… fast foods popping up everywhere. I feel the government is allowing all these shops to pop up a couple of yards away from each other, just to give you quick food (Felecia, school meals supervisor)

Maya:

They dump those things in our area because they see it as deprived and they think the people who live there don’t matter.

Leyla, who described the composition of her high street:

it’s keeping the adults on their liquor, the kids on the sweets and then the take-aways for dinner… It’s what we’re seeing everyday so all we think about is sweets and drinks… It’s like the betting shops. a lot more people are doing it… it’s not good.

Healthy, sustainable diets & food democracy

There are contradictions within The Plan which undermine its approach. Advancing healthy and sustainable diets are central to The Plan. It shows contradictions have arisen through free-market mechanisms that do not benefit dietary health (for example, the domination of school food by few multinational companies – see above ). It calls for increased competition such as around school food, then for this to be guided by more regulation. That is, increased state intervention for example, new Reference diet and certification projects for public sector procurement. ‘Obesity’ cannot be tackled unless policy changes a divisive narrative away from social ‘burden’ and tackles the multiple stigmas faced by people living with obesity. While The Plan was informed using participatory democracy methods the recommendations lacks food democracy in their implementation.

Reference diet

Shifting the country’s diet to be healthy and sustainable, dominated by plant-based foods is purposed by the recommended new Reference Diet as part of Good Food Bill (TP p163). It will underpin all public sector food standards and recommends that the requirement for meat to be provided three times a week is removed from the School Food Standards. This raises issues around why current system is failing and food democracy.

Failure of public sector procurement

We know the current – privatised – system is not working. Nutrient standards are replaced by food groups and infrastructure of public health nutritionists/dietitians replaced by nutrition advisors to big companies. Not all public bodies have to follow standards including schools and care homes (TP p253). The Plan provides is damning evidence on public sector food provisioning.

‘Much of the food served by public bodies is bad. Only 39% of primary school children who have to pay for school meals choose to eat them; while the main barrier for this is cost, another factor is that food is unappealing. In hospitals, 42% of patients rated the food as either satisfactory, poor or very poor; 39% of staff rated the food as poor. Over a third of the money hospitals spend on food goes on items that are thrown away uneaten. Food served in prisons is rated even worse: only 29% of inmates describe the food they receive as “good” or “very good”’ (TP p253)

This together with growing food insecurity gives a pessimistic outlook for maintaining population nutritional health. The Plan recommends strengthening procurement rules and using certification schemes, for example Soil for Life to ensure schools, hospitals, prison foods are healthy and sustainable according to the Reference Diet. These tools attempt to manage public sector food provisioning from corporate sector whose priorities are profits.

Food democracy is central in changing diets. Sixteen years ago, Jamie Oliver’s mission to improve school food standards met with protest from mothers when the changes to school menus were imposed. Mothers are aware of children’s dietary needs, their everyday eating habits and contribution can be made by school food.

A new Reference Diet should be fully discussed to ensure no population groups are failed. Little mention is made of diets of mothers and older people.

Changing behaviours: corporate and communities but not political?

Recommendations use mix of interventions that use fiscal levers and psychology, mostly resting on behavioural economics that aim for long term changes to the nation’s diet. Taxation on sugar and salt aimed at encouraging companies to reformulate food products has already been knocked back by the Prime Minster.

That food companies cannot be relied up to support our health runs throughout The Plan and includes using psychological means to influence eating patterns ‘consumption effect’ and advertising.

Behavioural economics provides data to back up the view that ‘UK does not place as high a social value on food and cooking as our continental neighbours’ (P1 p35). Missing is comment about the working patterns and hours of UK workers compared to those in the EU. For example, UK workers work longer hours and have shorter lunch breaks compared to Denmark and Germany but less than Singapore. Is the UK’s ‘eat quickly’ food culture (P1 p56) more to do with precarious work and work-life imbalance? How do school lunchtimes support social value around food and nutrition when these too are short and often do not support commensality (Macdiarmid et al., 2015)?

Food choices, as The Plan states, are complex, including psychology. It draws on the concept of ‘scarcity’ as example of the psychological: the notion that the stresses of living in deprivation constrains people’s ‘cognitive bandwidth’. So, policymakers help by making the healthy choice an easy one. Maybe, this is part of the thinking behind removing meat from school menus? However, a cash first approach would reduce the stresses of living in poverty. Surely the ethical response must be to reduce the stress and its health implications and not manipulate choice?

Of concern is whether The Plan’s focus on children’s diets and schools is an attempt to cast children as agents for change? Thus, the diets of mothers and the older people are largely ignored.

‘Obesity’, stigma and inequalities

The Plan focuses on diet-related illness especially ‘obesity’ that continues to be framed the major problem and burden on society rooted in lifestyle choices. A framing that produces blame and stigma.

Rightly, The Plan points to changes in the food system over time that promoted excess weight gain for people who are genetically susceptible, and nutritional and health inequalities. Using terminology from the system’s approach it places the public and food industry in ‘junk food cycle’ with ‘feedback loops’ that seemingly operate beyond our control – there is no immediate answer, just to wait for the market to correct itself:

But no country has successfully reversed the drift towards obesity. While some interventions are more effective than others, there is no single “silver bullet” … Given the power of the Junk Food Cycle, multiple interventions are needed … Today’s dietary patterns have formed over a period of at least 70 years. We will need long-term political commitments to reverse them (TP p55)

This fatalism is treated with cynicism, as exemplified by Leyla, in research with working- class parents of children with higher weights, who believes public health priorities are a matter of political choice:

government… if they put a shut down on what happens, on smoking or whatever, you will see a cut down drastically… if they wanted to make a change they could, but they’re choosing not to.

The Plan illustrates that ‘obesity’ is genetically driven and gives data that shows how affluent families are affected including through stigma. It underlines that the greatest impact is on lower income families. It illustrates maldistribution of food through existence of ‘food swamps’ and BOGOFs. It outlines the role of ultra-processed-foods and how ‘Scientists …have recorded 70,296 distinct biochemicals across the entire range of foods eaten by humans’ (TP p53). That said, it lacks a comprehensive ‘societal’ approach that would consider other factors such as the role of endocrine disrupting chemical (EDCs), sleep, and the stress, stigma and trauma caused by inequalities including structural racism that as part of everyday lives impact weight gain and health. Therefore, its core message is individual dietary behavioural change to support health.

Critically, there is no comment about endemic multiple stigmas and discrimination people living with ‘obesity’ face, including children and families (Noonan-Gunning, 2019). It ignores weight stigma research including recent literature by Stuart Flint and Weight Stigma colleagues about discrimination in access to health care and language. Instead, The Plan seems careless with language, using the word ‘fat’ without licence such as ownership by fat activist movements for body positivity, acceptance and neutrality. It is contradictory saying: But you don’t have to be fat to be made ill by bad diet (TP, p24) and later ‘This does not mean that some people are doomed to get fat’ (TP, p45). The problem is reduced to individual body shape and size: being ‘fat’. Counterposed is argument for body equality.

So, we ask what’s the problem ‘obesity or inequalities’? Meaningfully tackling inequalities in all its forms – food and nutrition, health & health access, structural racism & social rights – will solve many of the health conditions we face. The problem is not diversity in human body shapes and sizes. ‘Obesity’ is otherwise used to promote fear, scapegoating and social division.

Young mum Sam says:

I feel that the government are very quick to judge those who don’t fit a societal norm, but are unwilling to offer up any solution other than fat shaming…. I find it extremely hypocritical, especially given that this country’s leader also doesn’t fall into the ‘ideal weight’ category. Of course, at the other end of the scale, you have those who struggle massively to gain weight, who are also stigmatised. Those people are usually ones who have seen nothing but fat shaming and ‘ideal weight’ propaganda for most, if not all of their lives and are desperate to be classed as ‘normal’.

It’s important to remember that while tackling obe*ity is a big part of it, understanding ‘health at every size’ is a much better approach. Being told you’re constantly fat and ‘not normal’ or ‘healthy’ is massively detrimental to an individual’s mental wellbeing, which makes it that much harder for someone to focus on keeping themselves healthy and much more importantly-happy.

Investment needed

Austerity and local government spending cuts

Austerity policies are a core driver of the increase in inequalities especially since 2010 with severe cuts in local government funding and dismantling of welfare state. However, The Plan makes no reference to past policies. The public health nutrition (PHN) and food systems were unprepared for the pandemic. The foundations that would support a crisis had been eroded.

Austerity measures delivered a cut of 38% to local government budgets between 2009 and 2018, other estimates as high as 60% by 2020. Services that deliver public health nutrition and social nutrition were reduced to a minimum, privatised or charitised. This disinvestment in PHN Spending on Meals on Wheel was cut by 47%. and 1000 children centres closed. Green spaces are being used for development.

Councils that have long adopted market-led policies of best value and competitive tendering are in crisis or going bust. How can they meet demands of The Plan without services being fully funded by central government?

The Plan does not address the cuts in local government. There is no new investment. New investment is targeted to the PCNs for ‘Community Eat Well’. It is unclear if PCNs now take responsibility for community/public health nutrition, that is shifting responsibility away from public health within local authorities (LAs). It is assumed in the Good Food Bill that LAs take on recommendations, be part of ‘local level’ strategy and a ‘societal safety net’ with central government and NGOs (P1 p55). PCNs do not seem to be given responsibility within the Good Food Bill unless they come under ‘government’ (TP p163). The Plan illustrates responsibility for food policy is dispersed across government departments (TP p32). When responsibility is not clear, there is lack of governance and scrutiny. When it is not clear who has responsibility and where the burden lies it cannot be seen who escapes responsibility. The recommendations aim to tackle these governance issues but ambiguity remains. In these situations, those with least power – families and communities – often take responsibility due to morality, an ethic of collective care.

Conclusion

Radical change, state responsibility & Right to Food

How seriously does government take its responsibility in tackling household food insecurity and diet-related inequalities if it does not provide the resources around real living wage and hours, welfare rights and the Right to Food? How can food systems based on promoting health and sustainability be successful if government does not invest at every level? How are those with least resources expected to survive? The DWP have started to measure food insecurity while the Joseph Rowntree Foundation reports on destitution.

The Plan provides data showing that the public support state intervention – that the Government takes responsibility to tackle diet-related ill health, such as through taxation. Tackling food insecurity is seen as a state responsibility in research with the public health nutrition workforce (Noonan-Gunning et al., 2021).

Responsibility is an expression of care – yet this government is not a caring government. The cruel treatment of refugees crossing the English Channel is the tip of the iceberg. On another iceberg’s tip sits the cronysism of the government that was exposed during the pandemic as public assets transfer into private hands of privileged friends. This suggests the direction of travel is towards more authoritarian and divisive methods of government. The new Office for Health Promotion, follows the pathway to Singaporean system set by the authors of Britannia Unchained who are now in power. Singapore’s public health system is highly privatised, heavy use of apps as a ‘smart’ nation. This also means more surveillance, more big data collected on citizens. Singapore’s response to the pandemic exposed ‘extreme neoliberalism’ illustrated in its treatment of migrant workers. Not a model to follow!

I have no illusions about The Plan. I acknowledge that the business leaders behind it might tilt towards a different kind of capitalism – a kinder capitalism than UK neoliberalism. This is not the direction this government will take. Already it has said it will not use fiscal measures that could raise £2.9bn–£3.4bn (TP p195).

Small steps forwards are always welcomed but most of the recommendations to tackle diet-related inequalities are undermined because of the disconnect with austerity, crisis in local government spending and the ideological direction of this government. As set out above, there is failure to address underlying causes. So, in the Biblical sense the recommendations of The Plan are built on sand.

The way forward is to build the Right to Food campaign and organise in our communities to feed all in need. Grassroots social movements of communities and food and nutrition workforces can combine with NGOs and trade unions to convince government for changes that provide food and nutrition security and sustainable future for the planet.

The reality is that political parties/governments committed to redistributive policies, full employment and strong social welfare system are needed to tackle inequalities (Navarro and Shi, 2001). Further, food democracy that is based on the voices of grassroots communities and workforces is needed to enable policies and food economies to work in the interests of health. Example is provided from Brazil during 2003 – 2018, when the Worker’s Party and CONSEA – Brazil’s Food and Nutrition Security Council – organised for the Right to Adequate Food to be enshrined in the constitution in 2010, and led campaigns to eradicate hunger. Despite their successes CONSEA was eliminated by right wing government of Bolsonara in 2019.

What to do next

Support the Right to Food Campaign: https://www.ianbyrne.org/righttofood-campaign

Get active with Food Inequalities Rebellion: https://foodinequalitiesrebellion.wordpress.com/

Get organised and help feed people in your locality

Contact me: Sharon.noonan-gunning.1@city.ac.uk

Sources:

Coveney, J. (2006) Food, Morals and Meaning , The pleasure and anxiety of eating. Second edn. Oxon: Routledge.

Davies, J., Damani, P., Margetts, B (2009) Intervening to change the diets of low-income women Proceedings of the Nutrition Society (2009), 68, 210–215. doi:10.1017/S0029665109001128

Elkington, J (2020) Green Swans. The Coming Boom in Regenerative Capitalism. New York: Fast Company Press

Henderson, R. (2020) Reimagining Capitalism. How Business Can Save the World. London: Penguin

Macdiarmid, J., Wills, W., Masson, L.F., Craig, L.C.A. and Bromley, C. (2015) ‘Food and drink purchasing habits out of school at lunchtime: a national survey of secondary school pupils in Scotland’, International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12(98), pp.05/03/16-98.

Mazzucato, M (2021) Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism. London, UK: Allen Lane.

Navarro, V. and Shi, L. (2001) ‘The political context of social inequalities and health’, Social Science & Medicine, 52 pp.481-491.